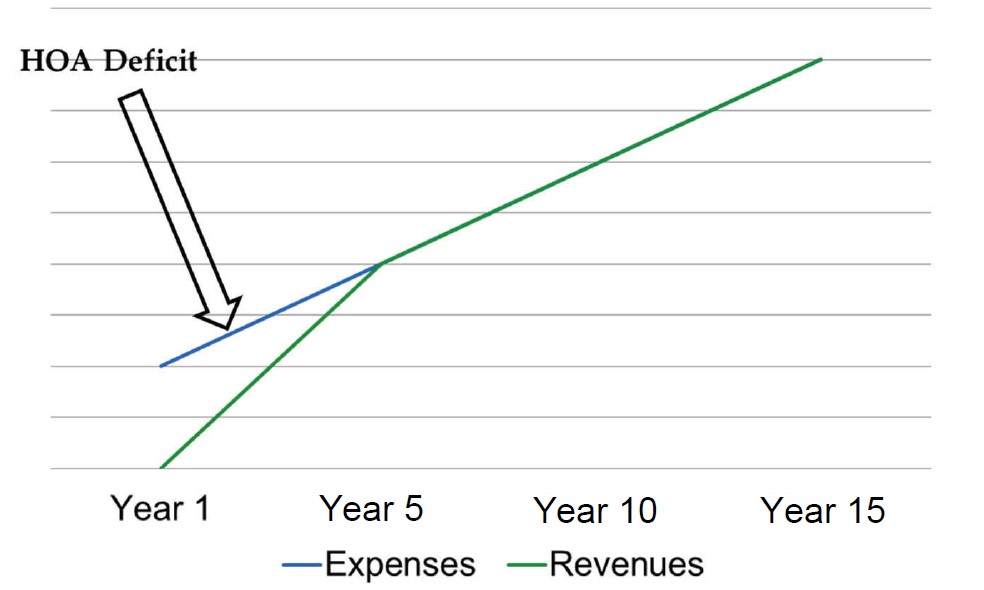

From the date of creation until death, a community association requires funds to operate. Operational funds for the association are obtained through assessments levied by the community association, but only as homes are built and conveyed to homeowners. As a result, in the early to mid-stages of a planned community life cycle, there will be an operational deficit until completed home sales reach a level that can support on-going operations.

Texas law imposes no requirement that a planned community developer pay assessments, nor does it require that the developer fund operational deficits. However, the developer will fund deficits since failure to fund will adversely impact marketing and sales. What are the factors that influence declarant subsidies and what steps should the developer take to, hopefully, minimize the subsidy?

Planning and the Full-Cycle Build-Out Budget

The most important step a developer can take to understand and plan for declarant subsidies is to prepare a “full-cycle” budget for the project. A full cycle budget projects association expenses during the development and final completion of the project. For the large planned community, the full-cycle budget is a projection. The developer and management company or budget consultant makes assumptions such as the projected number of homes or units, square footage of commercial areas (if a mixed-use community and if square footage is used to allocate costs to commercial), planned amenities and when those amenities will be completed and available for their intended use. A full-cycle budget includes annual estimates from the first year of operation, and each year thereafter until full build-out. In effect, the developer is creating an early estimate of the budget for each year of the project until completion. A full-cycle budget shows the operational deficit and required developer subsidy in each year of operation. The object is to project when association revenue from end-user assessments is sufficient to discharge projected costs. Ideally, the required deficit gradually declines well prior to completion of the project.

Early assumptions and costs used to prepare the initial full-cycle budget will change as the project develops. The developer and association manager or budget consultant should meet at least annually to update and review the full-cycle budget, reevaluate expectations regarding the amount and duration of the subsidy requirement, and consider adjusting association assessment revenue and/or expenses to manage the projected subsidy.

Dial in the Working Capital Contribution

It is customary to collect a “working capital assessment” at the closing of each lot from the builder to the end-user. For non-condominium product, working capital can be used to pay operational costs of the association while the developer controls the association. In other words, since the working capital can be used to pay association expenses, expenses paid from working capital collections reduces the declarant subsidy. Market expectations will set a limit on the amount of working capital that can be collected upon transfer of the lot, but since the amount of working capital results in a direct reduction of the declarant subsidy, the developer should consider right sizing the fee. Whatever the amount, the projected annual working capital collections from closings should be incorporated into the full-cycle budget.

Builder Exemptions

Often the developer will exempt builders from the payment of all or a portion of assessments for lots closed by the builder. To accurately project the developer subsidy, assessment concessions should be incorporated into the full-cycle budget, and the budget should be adjusted if the exemption changes as the project develops. Keep in mind that each dollar in assessments not paid by a builder directly increases the declarant subsidy. If an assessment exemption is granted, the developer should consider limiting the exemption to a specific time period, usually the period of time necessary for the builder to construct a home on the lot after closing. Also, once the project is stabilized from a marketing perspective, the developer should consider whether a builder assessment exemption is still needed to ensure project success.

Community Transfer Fee Covenant

While there are limitations in Texas on fees paid on the resale of property, there are no limitations if the funds are paid directly to the association. Often called a “community transfer fee”, this component of association revenue is different from the working capital fee described above, since the community transfer fee is not collected on the first sale from a builder to the end user and is calculated based on the resale price (usually the working capital fee is a fixed amount or a certain number of months of assessments, e.g., 2 months of regular assessments). The community transfer fee is often between 0.25 and 0.50 percent of the sales price of the home. Since the community transfer fee is collected only upon a resale, revenue from this fee will occur in later stages of the project. As a result, the fee has greater utility for purposes of reducing the declarant subsidy for larger projects with longer completion periods. However, just as, if not more important, is that the fee will continue to be collected by the association after project completion and reduces the risk of assessment increases and special assessments post-completion.

Disclaimer: Content contained within this publication provides information on general legal issues and is not intended to provide advice on any specific legal matter or factual situation. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking professional counsel.